Close

Our Products

All Products

Pleasure

Performance

Conditioning

Fibre

Breeding & Stud

Racing

Specialty

Supplements

Quick Feed finder

Free Diet Analysis

The Complete Range

Nutrition Centre

Articles

All About Fibre

Feeding for Condition

Competition Season

Laminitis

Breeding

Foal care

Building Topline

Gut Health

Senior horses

Racing & Breeding

Feeding in a Drought

Tools & Calculators

Competitions / Offers

Our Riders

Brand ambassadors

Junior Squad

About Barastoc

Why Barastoc

Our commitment

Barastoc's People

Our communities

Partnering with KER

Partnering with BHF

Sustainability

Find a Stockist

Contact Us

Ulceration of the Horse’s Gastro-Intestinal Tract

Although it’s not precisely known how many horses have ulcers reports of 25-50% of foals and 60-90% of performance horses have been quoted. It is likely, due to the probably causes of ulceration, that a significant proportion of leisure horses also suffer from the condition. In its worst case ulceration can also occur in the horse’s gullet and further down the intestine from the stomach, and may be differentiated, clinically by vets, under different names. But they all have a common starting point and this involves disruption of the normal physiology of the stomach.

The horse’s stomach constantly produces hydrochloric acid (HCl) from specialised cells. This is an extremely aggressive acid and is prevented from burning the stomach wall by a thick layer of mucus produced by goblet cells. These are both situated in the lower portion of the stomach. The role of acid in the stomach is to provide an environment for the pre-digestion of nutrients (for example coagulating protein and initial breakdown of carbohydrates) as well as stimulating enzyme release by the pancreas and small intestine wall when the stomach contents are evacuated into the ileum. As the stomach of the horse is small this, also, is a continuous process.

In the case of stomach ulcers the traditional theory is that acid secretion, coupled with disruptions in mucus production, mainly stress related, led to lesions that were exacerbated by contact with acid.

However recent research, as well as an increasing understanding of the role of bacteria in the stomach, has progressed this theory. Now it has been shown, additional to the above, that the fermentation of some products by the gastric microflora can have a role in ulcer production.

The pH of the stomach, maintained at a reasonable acidic level encourages the proliferation of a number of microbial species that will ferment nutrients, producing short chain fatty acids as their end products (VFA). Although this does not involve the type of bacteria that ferment fibre in the hind gut (here the environment is neutral to slightly acidic) those in the stomach can breakdown protein and starch, and one of the major end products released is lactic acid.

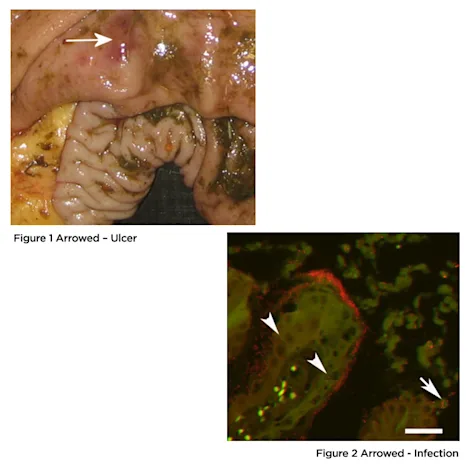

Lactic acid has been demonstrated to be able to penetrate the mucosal cells and this is thought to be another route for generating lesions (Figure 1). Additionally once a lesion has been created it becomes quickly infected with the bacteria (in red) that, although as yet unidentified, are thought to produce the lactic acid (Figure 2). Heliobacter, which are the primary culprit in human ulcers have been detected in horse’s stomachs.

As with any microbial system once the balance has been shifted it tends to reinforce itself. Therefore an increase of these lactic producers would be expected and these will escape into the intestine, creating their own micro-environment through lactic acid production and likely causing lesions along the small intestine. Although gastric ulcers grab the headlines in horses, ulceration along the whole small intestine are not uncommon.

Having previously quoted that the majority of domestic sources have, or may have, ulcers one significant statistic shows up. Horses on permanent pasture have a much lower incidence, and this fact provides the clue on what is happening.

In the natural state the horse grazes continuously. This means it is constantly chewing, producing saliva which is forced into the food and swallowed. The saliva contains sodium bicarbonate to help neutralise the stomach acid. and the forage has an intrinsic ability to bind up some of the acid (Acid Binding Capacity). Between them they maintain the stomach at reasonable acidity level somewhat akin to vinegar compared to the battery acid strength of the secreted HCl. At these levels the acid producing bacteria are suppressed. Even when stressed (being hunted, fighting during mating) these factors are short-lived and relatively infrequent.

In the case of the domesticated horse several factors are now introduced that disrupt normal function.

Firstly stress: Not necessarily what we would regard as stress, but an environment the horse finds itself in that does not encompass normal behavioural activity: Stabling, transport, unfamiliar surroundings and the more familiar stresses of disease, injury or pain. Of course we minimise this as far as we are able but some factors are unavoidable. The result of these stresses, whether intermittent (transport) or long term (being at the bottom – or top – of a social group) can be disruption of the production of mucus to line the stomach causing a breach in the defence against acid burns.

Secondly exercise: A wild horse will run if the stimulus is there and it will run on a “full stomach”. Performance horses tend to run on an empty stomach and so there is no saliva or forage to mop up the acid. Hard exercise constricts the stomach and pushes the acid up into the upper section that has little mucosal protection against acid burns. It is little wonder that up to 90% of racehorses suffer from ulcers.

Thirdly feeding: Constant feeding is not always an option. Even with a full hay net the introduction of “meals”, whether as hard feed or as cereals/proteins, will have an effect on stomach physiology and feeding behaviour. Removal of feed during stress periods will also have an impact. There will be periods where acid production has little or nothing to act on, or encourages microbial breakdown of high starch feeds releasing factors which promote the potential for ulcers.

So if we have a horse that is not constantly grazing, and experiences one or many of the above factors, there is a possibility that is will be prone to ulcers. So what can we do to help?

Obviously there are husbandry methods we can use. Maintaining routine, avoiding obvious stresses whenever possible and treating injury are all positive actions. However we need to think about feeding as well. So how do we protect the stomach, gullet and intestine from the actions of penetrating acids and infections?

Water. Feeding a moist feed will maintain saliva flow. For every litre a horse drinks four litres are produced by the saliva and gastric secretions and later re-absorbed. If water is restricted, especially when eating dry feed saliva may be compromised. A horse will drink but not when it is chewing and it is at this time when moisture is needed to allow the flow of bicarbonate from the saliva. Moist feed also produces a more even intake of water, and a constant intake of water, will dilute the stomach acid and improve the buffering capacity of the saliva.

Minimise starchy materials. Starch is an excellent provider of energy and is convenient to feed, but overfeeding is associated with many disorders. In the stomach starch has a relatively low Acid Binding Capacity (ABC), is not good at soaking up stomach acid, and will act as “fuel” for those bacteria that thrive in more acidic conditions.

Introduce feeds with a high ABC such as legume hays and soluble fibres. For example, at an acid level of pH4, the level that a normally functioning stomach should be, and at pH 3, which is in the “problem” region: Cereals Legumes, including lucerne Pulp Products, including Beet Pulp

ABC@pH 4 72-110 280 640 200-370 meq/kg

ABC@pH3 180-400 470-1070 480-880 meq/kg

ABC increases as acidity increases and so helps combat excessive acid build up.

Protect the mucosal lining. Although there are proprietary brands available, one of the most widely reported nutrients that can help is pectin. In acidic conditions pectin alters its structure to one that is similar to mucus and it has been shown to bind to, and thicken, the stomach mucosa. In the presence of surfactants (naturally occurring soaps that emulsify oils and water) the effect is enhanced.

So, ideally, a feed that contains legumes, pectins and surfactants, and which can be fed as a wet feed would be the best possible complementary feed for forage. It would also have to have low levels of starch but provide sufficient energy to replace cereals or hard feed and reduce the overall starch load.

Barastoc and British Horse Feeds have two such products:

Speedi-Beet, high in pectins and with a good acid binding capacity, can replace starchy feeds and provide a high moisture ration that has the ability to coat the stomach wall and soak up excess acid.

Barastoc Fibre-Beet Mash, incorporating Speedi-Beet with lucerne and oat fibre, has a higher ABC and good levels of surfactants (Oat is one of the richest sources of surfactants – one of the reasons it binds cholesterol in humans), will provide good protection.

The choice of which product to use will be influenced by your preferred feeding regime, but both will be useful in offsetting the threat of ulcers.